Falcoaria faz parte da vida do deserto .

livro de Edward Henderson, “Arabian Destiny”, Motivate Publishing, 1999. Page 91.

Falconry is an integral part of desert life which has been practiced in the UAE for centuries. Originally, falcons were used for hunting, to supplement the Bedouin diet with some meat, such as hare or houbara. Both Sheikh Zayed and Sheikh Mohammed have shown great concern and support for this important part of the UAE’s cultural heritage.

In the time before the UAE was formed, and before the discovery of oil allowed the development of roads and communication systems, hunting expeditions were also frequently used as a way for the tribal sheikhs to ‘tour’ their territory and keep in touch with the latest developments in areas which were otherwise incommunicado. The sheikh would hunt during the day, then a desert majlis would be held around the campfire in the evenings, when the Bedouin would come to pay their respects and raise with him any matters of concern.

Nowadays, falconry is practiced purely for sport. The main prey for falcons in the UAE are MacQueen’s bustard, houbara, or hare. There is now a very successful captive breeding programme in the UAE for houbara, ensuring that this popular sport does not eliminate this species.

The two main species of falcon kept in the UAE are the saker and the peregrine. The trapping and training of falcons requires skill, patience and a considerable amount of bravery. The potential danger, of course, is part of the attraction, as is the opportunity to have a close-up view of the power, grace and beauty of a falcon in flight.

In his autobiography, “Arabian Destiny”, Edward Henderson gives a fascinating eyewitness account of the old method of acquiring a new falcon (these days they are more commonly bought than captured).

“I have seen a falcon catcher at work, near Dubai. He makes a deep hole in the sand, covered with branches, and in this he hides. String, some hundred yards long, is run out

through steel loops set in the sand in the shape of a rather open ‘L’. At the corner a net is set across the angle, lying flat on the sand in such a way that, when the string is pulled, it swings upwards and over to come down on the sand within the L-shape. At this point there is a loop in the sand and another string. One end of this string goes to the catcher in his hole, and at the other is a pigeon secured by a leg. The catcher, when he sees a falcon, lets the pigeon go a little way and it flies trailing the string. The falcon takes a good look and if the catcher is well concealed, will stoop at the pigeon, which the catcher pulls back to the hoop. As the falcon seizes the pigeon and digs his beak into it, the catcher pulls it home to the ring and releases the net, which springs up and over the falcon and pigeon together. The catcher then comes up out of the hole and walks across to sort it all out.” 1

Once a falcon is acquired, the falconer sets about taming and training it. A leather hood is used to cover the falcon’s eyes and the bird is deprived of food in order to make it easier to tame. In the first few weeks, the falconer remains with the falcon all the time to establish as close a relationship as possible with the bird. The bird is restrained by tethers around its ankles. During the day the bird perches on the falconer’s leather sleeve while the falconer holds the tethers, and is always kept near the lure – a bundle of feathers. By night, the tethers are attached by a shorter cord to a swivel on a small mushroom-shaped wooden perch on a stake in the sand. This allows the falcon a certain freedom of movement, whilst ensuring that it cannot escape. The falconer names the bird and constantly calls to it so that it comes to recognise his voice from great distances.

Initial training consists of removing the hood and allowing the bird to move from the perch to the falconer’s hand, whilst held by its leg restraints. Eventually the bird will begin to make short flights. The falconer will take the lure and some raw meat around 100 yards away from the bird and one of his associates will remove the bird’s hood, whilst the falconer calls the bird’s name and swings the lure. The bird flies over and catches the lure, whereupon the falconer rewards it with some meat.

Later still, the training will incorporate live prey, such as a tethered pigeon, which the falcon will be allowed to swoop at before the falconer lures it away with meat. This part of the training is very important for Islamic hunters as it teaches the falcon not to kill its prey immediately. In order for the hunters to be able to eat the prey in accordance with their beliefs, it must still be alive when its throat is cut and blood is drawn. Once properly trained, a falcon will hold a captured bustard for quite some time without killing it, although the hunters must reward it immediately with food for doing so.

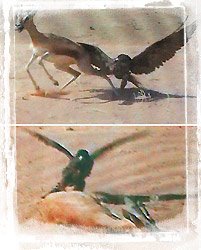

In February 2003, one of the most remarkable events in the recorded history of falconry took place when a falcon owned by Sheikh Mohammed brought down a deer many times its own weight.

The hunt was a long and arduous one. When the falcon finally captured the deer, it is reported to have lifted it several times. This is thought to be the first time that a falcon has taken a deer.In modern times, falconry in the UAE has incorporated new technology that benefits birds and owners alike. Falconry is strictly controlled by both federal and local emirate laws, to ensure proper treatment of the birds. Only a few decades ago, the most successful falcons would be kept in captivity for several years, although the hunting season only ran through the winter months. Nowadays, under the direction of the Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency (ERWDA), the Sheikh Zayed Falcon Release Project is responsible for returning falcons to the wild at the end of the annual hunting season. The project was initiated as a result of Sheikh Zayed’s desire that the falcons he used for hunting every year should not become completely domesticated, but should continue to live in their natural state. The selected birds are placed in isolation at the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital, where they are given full medical check-ups to ensure that only completely healthy birds enter the wild population.

Each bird has a microchip inserted beneath its skin, as an aid to future identification, and anumbered ring fitted on its leg, as part of the Emirates Bird Ringing Scheme. The falcons are then put through a rigorous exercise programme, to ensure that they are released in peak condition. They receive extra food to increase their weight and their chances of survival in their first weeks back in the wild. The birds are then transported from the UAE to an area along the migratory routes of other falcons, where they are released.

This project also incorporates the latest technology in order to provide scientists with data regarding migratory patterns. Some of the falcons are fitted with miniature satellite transmitters so that their movements can be tracked.

The respect of the people of the Emirates for their country’s heritage, and the support offered by Sheikh Zayed and Sheikh Mohammed, means falconry has not only survived the process of modernisation which the country has undergone, but has prospered.

In the time before the UAE was formed, and before the discovery of oil allowed the development of roads and communication systems, hunting expeditions were also frequently used as a way for the tribal sheikhs to ‘tour’ their territory and keep in touch with the latest developments in areas which were otherwise incommunicado. The sheikh would hunt during the day, then a desert majlis would be held around the campfire in the evenings, when the Bedouin would come to pay their respects and raise with him any matters of concern.

Nowadays, falconry is practiced purely for sport. The main prey for falcons in the UAE are MacQueen’s bustard, houbara, or hare. There is now a very successful captive breeding programme in the UAE for houbara, ensuring that this popular sport does not eliminate this species.

The two main species of falcon kept in the UAE are the saker and the peregrine. The trapping and training of falcons requires skill, patience and a considerable amount of bravery. The potential danger, of course, is part of the attraction, as is the opportunity to have a close-up view of the power, grace and beauty of a falcon in flight.

In his autobiography, “Arabian Destiny”, Edward Henderson gives a fascinating eyewitness account of the old method of acquiring a new falcon (these days they are more commonly bought than captured).

“I have seen a falcon catcher at work, near Dubai. He makes a deep hole in the sand, covered with branches, and in this he hides. String, some hundred yards long, is run out

through steel loops set in the sand in the shape of a rather open ‘L’. At the corner a net is set across the angle, lying flat on the sand in such a way that, when the string is pulled, it swings upwards and over to come down on the sand within the L-shape. At this point there is a loop in the sand and another string. One end of this string goes to the catcher in his hole, and at the other is a pigeon secured by a leg. The catcher, when he sees a falcon, lets the pigeon go a little way and it flies trailing the string. The falcon takes a good look and if the catcher is well concealed, will stoop at the pigeon, which the catcher pulls back to the hoop. As the falcon seizes the pigeon and digs his beak into it, the catcher pulls it home to the ring and releases the net, which springs up and over the falcon and pigeon together. The catcher then comes up out of the hole and walks across to sort it all out.” 1

Once a falcon is acquired, the falconer sets about taming and training it. A leather hood is used to cover the falcon’s eyes and the bird is deprived of food in order to make it easier to tame. In the first few weeks, the falconer remains with the falcon all the time to establish as close a relationship as possible with the bird. The bird is restrained by tethers around its ankles. During the day the bird perches on the falconer’s leather sleeve while the falconer holds the tethers, and is always kept near the lure – a bundle of feathers. By night, the tethers are attached by a shorter cord to a swivel on a small mushroom-shaped wooden perch on a stake in the sand. This allows the falcon a certain freedom of movement, whilst ensuring that it cannot escape. The falconer names the bird and constantly calls to it so that it comes to recognise his voice from great distances.

Initial training consists of removing the hood and allowing the bird to move from the perch to the falconer’s hand, whilst held by its leg restraints. Eventually the bird will begin to make short flights. The falconer will take the lure and some raw meat around 100 yards away from the bird and one of his associates will remove the bird’s hood, whilst the falconer calls the bird’s name and swings the lure. The bird flies over and catches the lure, whereupon the falconer rewards it with some meat.

Later still, the training will incorporate live prey, such as a tethered pigeon, which the falcon will be allowed to swoop at before the falconer lures it away with meat. This part of the training is very important for Islamic hunters as it teaches the falcon not to kill its prey immediately. In order for the hunters to be able to eat the prey in accordance with their beliefs, it must still be alive when its throat is cut and blood is drawn. Once properly trained, a falcon will hold a captured bustard for quite some time without killing it, although the hunters must reward it immediately with food for doing so.

In February 2003, one of the most remarkable events in the recorded history of falconry took place when a falcon owned by Sheikh Mohammed brought down a deer many times its own weight.

The hunt was a long and arduous one. When the falcon finally captured the deer, it is reported to have lifted it several times. This is thought to be the first time that a falcon has taken a deer.In modern times, falconry in the UAE has incorporated new technology that benefits birds and owners alike. Falconry is strictly controlled by both federal and local emirate laws, to ensure proper treatment of the birds. Only a few decades ago, the most successful falcons would be kept in captivity for several years, although the hunting season only ran through the winter months. Nowadays, under the direction of the Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency (ERWDA), the Sheikh Zayed Falcon Release Project is responsible for returning falcons to the wild at the end of the annual hunting season. The project was initiated as a result of Sheikh Zayed’s desire that the falcons he used for hunting every year should not become completely domesticated, but should continue to live in their natural state. The selected birds are placed in isolation at the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital, where they are given full medical check-ups to ensure that only completely healthy birds enter the wild population.

Each bird has a microchip inserted beneath its skin, as an aid to future identification, and anumbered ring fitted on its leg, as part of the Emirates Bird Ringing Scheme. The falcons are then put through a rigorous exercise programme, to ensure that they are released in peak condition. They receive extra food to increase their weight and their chances of survival in their first weeks back in the wild. The birds are then transported from the UAE to an area along the migratory routes of other falcons, where they are released.

This project also incorporates the latest technology in order to provide scientists with data regarding migratory patterns. Some of the falcons are fitted with miniature satellite transmitters so that their movements can be tracked.

The respect of the people of the Emirates for their country’s heritage, and the support offered by Sheikh Zayed and Sheikh Mohammed, means falconry has not only survived the process of modernisation which the country has undergone, but has prospered.